User Guide¶

This page explains how to use the most common of the implemented models.

Each model corresponds to a differents structured prediction task, or possibly

a different parametrization of the model. As such, the training data X and

training labels Y has slightly different forms for each model.

A model is given by four functions, joint_feature, inference, loss

and loss_augmented_inference. If you just want to use the included models,

you don’t need to worry about these, and can just use the fit, predict interface

of the learner.

Details on model specification¶

For those interested in what happens behind the scenes, or those who might want to

adjust a model, there is a short explanation of these functions for each model below.

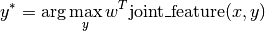

For all models, the joint_feature(x, y) function takes a data point and a

tentative prediction, and computes a continuous vector of a fixed length that

captures the relation between features and label. Learning (that is

learner.fit(X, y)) will learn a parameter vector w, and predictions

will be made using

That means the number of parameters in the model is the same as the

dimensionality of joint_feature.

The actual maximization is performed in the inference(x, w) function, which

takes a sample x and a parameter vector w and outputs a y^*,

which (at least approximately) maximizes the above equation.

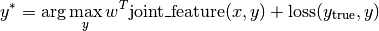

The loss(y_true, y_pred) function gives a numeric loss for a ground truth

labeling y_true and a prediction y_pred, and finally

loss_augmented_inference(x, y, w) gives an (approximate) maximizer for

A good place to understand these definitions is Multi-class SVM.

Note

Currently all models expect labels to be integers from 0 to n_states (or n_classes). Starting labels at 1 or using other labels might lead to errors and / or incorrect results.

Note

None of the model include a bias (intercept) by default. Therefore it is usually a good idea to add a constant feature to all feature vectors, both for unary and pairwise features.

Multi-class SVM¶

A precursor for structured SVMs was the multi-class SVM by Crammer and Singer. While in practice it is often faster to use an One-vs-Rest approach and an optimize binary SVM, this is a good hello-world example for structured predicition and using pystruct. In the case of multi-class SVMs, in contrast to more structured models, the labels set Y is just the number of classes, so inference can be performed by just enumerating Y.

Lets say we want to classify the classical iris dataset. There are three classes and four features:

>>> import numpy as np

>>> from sklearn.datasets import load_iris

>>> iris = load_iris()

>>> iris.data.shape, iris.target.shape

((150, 4), (150,))

>>> np.unique(iris.target)

array([0, 1, 2])

We split the data into training and test set:

>>> from sklearn.cross_validation import train_test_split

>>> X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

... iris.data, iris.target, test_size=0.4, random_state=0)

The Crammer-Singer model is implemented in models.MultiClassClf.

As this is a simple multi-class classification task, we can pass in training data

as numpy arrays of shape (n_samples, n_features) and training labels as

numpy array of shape (n_samples,) with classes from 0 to 2.

For training, we pick the learner learners.NSlackSSVM, which works

well with few samples and requires little tuning:

>>> from pystruct.learners import NSlackSSVM

>>> from pystruct.models import MultiClassClf

>>> clf = NSlackSSVM(MultiClassClf())

The learner has the same interface as a scikit-learn estimator:

>>> clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

NSlackSSVM(C=1.0, batch_size=100, break_on_bad=False, check_constraints=True,

inactive_threshold=1e-05, inactive_window=50, logger=None,

max_iter=100, model=MultiClassClf(n_features=4, n_classes=3),

n_jobs=1, negativity_constraint=None, show_loss_every=0,

switch_to=None, tol=0.001, verbose=0)

>>> clf.predict(X_test)

array([2, 1, 0, 2, 0, 2, 0, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 2, 1, 0,

0, 2, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 2, 2, 0, 2, 2, 1, 0, 2, 1, 1, 2, 0, 2, 0, 0, 1,

2, 2, 2, 2, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 1, 2])

>>> clf.score(X_test, y_test)

0.96...

Details on the implementation¶

For this simple model, the joint_feature(x, y) is a vector of size n_features * n_classes,

which corresponds to one copy of the input features for each possibly class.

For any given pair (x, y) the features in x will be put at the position corresponding

to the class in y.

Correspondingly, the weights that are learned are one vector of length n_features for each class:

w = np.hstack([w_class_0, ..., w_class_1]).

For this simple model, and inference is just the argmax over the inner product with each of these w_class_i:

>>> y_pred = np.argmax(np.dot(w.reshape(n_classes, n_features), x))

To perform max-margin learning, we also need the loss-augmented inference. PyStruct has an optimized version, but a pure python version would look like this:

>>> scores = np.dot(w.reshape(n_classes, n_features), x)

>>> scores[np.arange(n_classes) != y] += 1

>>> y_pred = np.argmax(scores)

Essentialy the response (score / energy) of wrong label is down weighted by 1, the loss of doing an incorrect prediction.

Multi-label SVM¶

A multi-label classification task is one where each sample can be labeled with any number of classes. In other words, there are n_classes many binary labels, each indicating whether a sample belongs to a given class or not. This could be treated as n_classes many independed binary classification problems, as the scikit-learn OneVsRest classifier does. However, it might be beneficial to exploit correlations between labels to achieve better generalization.

In the scene classification dataset, each sample is a picture of an outdoor scene, representated using simple color aggregation. The labels characterize the kind of scene, which can be “beach”, “sunset”, “fall foilage”, “field”, “mountain” or “urban”. Each image can belong to multiple classes, such as “fall foilage” and “field”. Clearly some combinations are more likely than others.

We could try to model all possible combinations, which would result in a 2 ** 6

= 64 class multi-class classification problem. This would allow us explicitly model all correlations between labels,

but it would prevent us from predicting combinations that don’t appear in the training set.

Even if a combination did appear in the training set, the numer of samples in each class would be very small.

A compromise between modeling all correlations and modelling no correlations is modeling only pairwise correlations,

which is the approach implemented in models.MultiLabelClf.

The input to this model is similar to the Multi-class SVM, with the training data X_train simple

a numpy array of shape (n_samples, n_features) and the training labels a binary indicator matrix

of shape (n_samples, n_classes):

>>> from pystruct.datasets import load_scene

>>> scene = load_scene()

>>> X_train, X_test = scene['X_train'], scene['X_test']

>>> y_train, y_test = scene['y_train'], scene['y_test']

>>> X_train.shape

(1211, 294)

>>> y_train.shape

(1211, 6)

We use the learners.NSlackSSVM learner, passing it the models.MultiLabelClf model:

>>> from pystruct.learners import NSlackSSVM

>>> from pystruct.models import MultiLabelClf

>>> clf = NSlackSSVM(MultiLabelClf())

Training looks as before, only that y_train is now a matrix:

>>> # clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

>>> # clf.predict(X_test)

>>> # clf.score(X_test, y_test)

With only 64 possible label-combinations, we can actually enumerate all states. Unfortunately, in general, inference in a fully connected binary graph is in gerneral NP-hard, so we might need to rely on approximate inference, like loopy believe propagation or AD3.

An alternative to using approximate inference for larger numbers of labels is to not create a fully connected graph,

but restrict ourself to pairwise interactions on a tree over the labels. In the above example of outdoor scenes,

some labels might be informative about others, maybe a beach picture is likely to be of a sunset, while

an urban scene might have as many sunset as non-sunset samples. The optimum tree-structure for such a problem

can easily be found using the Chow-Liu tree, which is simply the maximum weight spanning tree over the graph, where

edge-weights are given by the mutual information between labels on the training set.

You can use the Chow-Liu tree method simply by specifying edges="chow_liu".

This allows us to use efficient and exact max-product message passing for

inference:

>>> clf = NSlackSSVM(MultiLabelClf(edges="chow_liu"))

Training looks as before, only that y_train is now a matrix:

>>> # clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

>>> # clf.predict(X_test)

>>> # clf.score(X_test, y_test)

This model for multi-label classification with full connectivity is taken from the paper T. Finley, T. Joachims, Training Structural SVMs when Exact Inference is Intractable.

Details on the implementation¶

The model creates a graph over n_classes binary nodes, together with edges

between each pair of classes. Each binary node has represents one class, and

therefor will get its own column in the weight-vector, similar to the

crammer-singer multi-class classification.

In addition, there is a pairwise weight between each pair of labels. This leads to a feature function of this form:

The implementation of the inference for this model creates a graph with unary potentials (given by the inner product of features and weights), and pairwise potentials given by the pairwise weight. This graph is then passed to the general graph-inference, which runs the selected algorithm.

Conditional-Random-Field-like graph models¶

The following models are all pairwise models over nodes, that is they model a

labeling of a graph, using features at the nodes, and relation between

neighboring nodes. The main assumption in these models in PyStruct is that

nodes are homogeneous, that is they all have the same meaning. That means that

each node has the same number of classes, and these classes mean the same

thing. In practice that means that weights are shared across all nodes and

edges, and the model adapts via features.

This is in contrast to the models.MultiLabelClf, which builds a binary graph

were nodes mean different things (each node represents a different class), so

they do not share weights.

Note

I call these models Conditional Random Fields (CRFs), but this a slight abuse of notation, as PyStruct actually implements perceptron and max-margin learning, not maximum likelihood learning. So these models might better be called Maximum Margin Random Fields. However, in the computer vision community, it seems most pairwise models are called CRFs, independent of the method of training.

ChainCRF¶

One of the most common use-cases for structured prediction is chain-structured

outputs, implemented in models.ChainCRF. These occur naturaly in

sequence labeling tasks, such as Part-of-Speech tagging or named entity

recognition in natural language processing, or segmentation and phoneme

recognition in speech processing.

As an example dataset, we will use the toy OCR dataset letters. In this dataset, each sample is a handwritten word, segmented into letters. This dataset has a slight oddity, in that the first letter of every word was removed, as it was capitalized, and therefore different from all the other letters.

Each letter is a node in our chain, and neighboring letters are connected with

an edge. The length of the chain varies with the number of letters in the

word. As in all CRF-like models, the nodes in models.ChainCRF all have

the same meaning and share parameters.

The letters dataset comes with prespecified folds, we take one fold to be the training set, and the rest to be the test set, as in Max-Margin Markov Networks:

>>> from pystruct.datasets import load_letters

>>> letters = load_letters()

>>> X, y, folds = letters['data'], letters['labels'], letters['folds']

>>> X, y = np.array(X), np.array(y)

>>> X_train, X_test = X[folds == 1], X[folds != 1]

>>> y_train, y_test = y[folds == 1], y[folds != 1]

>>> len(X_train)

704

>>> len(X_test)

6173

The training data is a array of samples, where each sample is a numpy array of

shape (n_nodes, n_features). Here n_nodes is the length of the input

sequence, that is the length of the word in our case. That means the input

array actually has dtype object. We can not store the features in a simple

array, as the input sequences can have different length:

>>> X_train[0].shape

(9, 128)

>>> y_train[0].shape

(9,)

>>> X_train[10].shape

(7, 128)

>>> y_train[10].shape

(7,)

Edges don’t need to be specified, as the input features are assumed to be in the order of the nodes in the chain.

The default inference method is max-product message passing on the chain (aka

viterbi), which is always exact and efficientl. We use the

learners.FrankWolfeSSVM, which is a very efficient learner when

inference is fast:

>>> from pystruct.models import ChainCRF

>>> from pystruct.learners import FrankWolfeSSVM

>>> model = ChainCRF()

>>> ssvm = FrankWolfeSSVM(model=model, C=.1, max_iter=10)

>>> ssvm.fit(X_train, y_train)

FrankWolfeSSVM(C=0.1, batch_mode=False, check_dual_every=10,

do_averaging=True, line_search=True, logger=None, max_iter=10,

model=ChainCRF(n_states: 26, inference_method: max-product),

n_jobs=1, random_state=None, sample_method='perm',

show_loss_every=0, tol=0.001, verbose=0)

>>> ssvm.score(X_test, y_test)

0.78...

Details on the implementation¶

The unary potentials in each node are given as the inner product of the features at this node (the input image) with the weights (which are shared over all nodes):

The pairwise potentials are identical over the whole chain and given simply by the weights:

In principle it is possible to also use feature in the pairwise potentials.

This is not implemented in the models.ChainCRF, but can be done using

EdgeFeatureGraphCRF.

GraphCRF¶

The models.GraphCRF model is a generalization of the ChainCRF to

arbitray graphs. While in the chain model, the direction of the edge is

usually important, for many graphs, the direction of the edge has no semantic

meaning. Therefore, by default, the pairwise interaction matrix of the

models.GraphCRF is forced to be symmetric.

Each training sample for the models.GraphCRF is a tuple (features,

edges), where features is a numpy array of node-features (of shape

(n_nodes, n_features)), and edges is a array of edges between nodes, of

shape (n_edges, 2). Each row of the edge array are the indices of the two

nodes connected by the edge, starting from zero.

To reproduce the models.ChainCRF model above with models.GraphCRF, we can simply

generate the indices of a chain:

>>> features, y, folds = letters['data'], letters['labels'], letters['folds']

>>> features, y = np.array(features), np.array(y)

>>> features_train, features_test = features[folds == 1], features[folds != 1]

>>> y_train, y_test = y[folds == 1], y[folds != 1]

For a single word made out of 9 characters:

>>> features_0 = features_train[0]

>>> features_0.shape

(9, 128)

>>> n_nodes = features_0.shape[0]

>>> edges_0 = np.vstack([np.arange(n_nodes - 1), np.arange(1, n_nodes)])

>>> edges_0

array([[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7],

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]])

>>> x = (features_0, edges_0)

For the whole training dataset:

>>> f_t = features_train

>>> X_train = [(features_i, np.vstack([np.arange(features_i.shape[0] - 1), np.arange(1, features_i.shape[0])]))

... for features_i in f_t]

>>> X_train[0]

(array([[0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0],

...,

[0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, ..., 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 1, ..., 0, 1, 1]], dtype=uint8), array([[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7],

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]]))

Now we can fit a (directed) models.GraphCRF on this data:

>>> from pystruct.models import GraphCRF

>>> from pystruct.learners import FrankWolfeSSVM

>>> model = GraphCRF(directed=True, inference_method="max-product")

>>> ssvm = FrankWolfeSSVM(model=model, C=.1, max_iter=10)

>>> ssvm.fit(X_train, y_train)

FrankWolfeSSVM(C=0.1, batch_mode=False, check_dual_every=10,

do_averaging=True, line_search=True, logger=None, max_iter=10,

model=GraphCRF(n_states: 26, inference_method: max-product),

n_jobs=1, random_state=None, sample_method='perm',

show_loss_every=0, tol=0.001, verbose=0)

Details on the implementation¶

The potentials are the same as in the ChainCRF model, with unary potentials given as a shared linear function of the features, and pairwise potentials the same for all nodes.

EdgeFeatureGraphCRF¶

This model is the most general of the CRF models, and contains all other CRF models as a special case. This model assumes again that the parameters of the potentials are shared over all nodes and over all edges, but the pairwise potentials are now also computed as a linear function of the features.

Each training sample for models.EdgeFeatureGraphCRF is a tuple

(node_features, edges, edge_features), where node_features is a numpy

array of node-features (of shape (n_nodes, n_node_features)), edges is

a array of edges between nodes, of shape (n_edges, 2) as in

GraphCRF, and edge_features is a feature for each edge, given as a

numpy array of shape (n_edges, n_edge_features).

The edge features allow the pairwise interactions to be modulated by the context. Two features important for image segmentation, for example, are color differences between the (super)pixels at given nodes, and whether one is above the other. If two neighboring nodes correspond to regions of simlar color, they are more likely to have the same label. For the vertical direction, a node above a node representing “sky” is more likely to also represent “sky” than “water”.

A great example of the importance of edge features is Conditional Interactions on the Snakes Dataset.

Latent Variable Models¶

Latent variable models are models that involve interactions with variables that are not observed during training. These are often modelling a “hidden cause” of the data, which might make it easier to learn about the actual observations.

Latent variable models are usually much harder to fit than fully observed

models, and require fitting using either learners.LatentSSVM, or

learners.LatentSubgradientSSVM. learners.LatentSSVM alternates between

inferring the unobserved variables with fitting any of the other SSVM models

(such as learners.OneSlackSSVM). Each iteration of this alternation is as

expensive as building a fully observed model, and good initialization can be

very important. This method was published in Learning Structural SVMs with

Latent Variables.

The learners.LatentSubgradientSSVM approach tries to reestimate the latent

variables for each batch, and corresponds to a subgradient descent on the

non-convex objective involving the maximization over hidden variables. I am

unaware of any literature on this approach.

How to Write Your Own Model¶

TODO

Tips on Choosing a Learner¶

There is an extensive benchmarking in my thesis, TODO.

SubgradientSSVM : Good for many datapoints, fast inference. Usually worse than FrankWolfeSSVM, but takes less memory. Good for obtaining reasonable solutions fast. NSlackSSVM : Good for very few datapoints (hundreds), slow inferece. Good for obtaining high precision solutions. OneSlackSSVM : Good for mid-size data sets (thousands), slow inference. Good for obtaining high precision solutions. FrankWolfeSSVM : Good for fast inference, large datasets. Good for obtaining reasonable solutions fast.

Tips on Choosing an Inference Algorithm¶

TODO